CPSC 324, Spring 2004

Lab 5: Last Look at GIMP

THIS LAB gives you one last look at the Gimp, before we move permanently on to three-dimensional graphics. The exercise for the lab are two fairly substantial projects in image composition. These projects will use various Gimp tools, including some that we have not seen before. Much of this page is devoted to discussion of these tools. The actual projects are at the end.

The assignment for this lab is to complete the "Winter-To-Spring" and "Funny Money" projects that are described at the end of this lab. Post your final images on your Web site, along with explanations of how the project was done. You can include original images or links to them if you like, but this is not required. The images that you need can be found in /home/cs324/lab5 or you can download them using links on this page.

Color Correction with the Curves Dialog

You have already looked at the Levels dialog, which allows you

to adjust the colors and brightness levels of an image. Gimp has

a similar but more sophisticated tool for color correction:

the Curves dialog. To open this dialog, go to the "Tools"

menu of an image window, then to the "Color Tools" submenu,

and select the "Curves" command.

You have already looked at the Levels dialog, which allows you

to adjust the colors and brightness levels of an image. Gimp has

a similar but more sophisticated tool for color correction:

the Curves dialog. To open this dialog, go to the "Tools"

menu of an image window, then to the "Color Tools" submenu,

and select the "Curves" command.

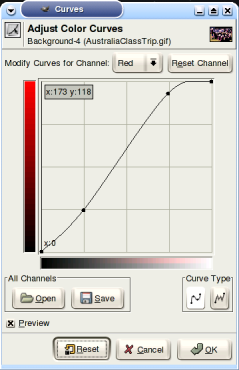

Both Levels and Curves allow you to set up a mapping of current color values to new color values. If you make an adjustment to the Red component of the color, for example, then the red component of each pixel will be replaced by a new value based on the mapping that you have defined. The Levels dialog can set up only fairly simple mappings. The Curves dialog can define arbitrary mappings. This is important because, for example, pixels with a lot of red might need one type of adjustment, while pixels with only a little red might need another type of adjustment, and pixels with a medium amount might need no adjustment at all. (And, by the way, if there is a selection, then Levels and Curves apply only to the selected region. This allows even finer control if you need it.)

The Curves dialog allows you to define mappings for the Red, Green, Blue, Alpha, and Value components of a color (where Value affects the overall brightness). A mapping is defined by a curve like the one shown in the picture. Current color values are along the horizontal axis, and new color values are along the vertical axis. The curve defines what new value will replace each current value. You can drag the points on the curve, including the endpoints. The coordinates of the point that you are dragging are shown in the upper left corner of the graph area. In the picture, a point was dragged to position (190,237) is on the graph. This means that pixels that currently have a red value of 190 will be modified so that their red value becomes 237. If you have some numerical values for the changes that you want to make, you can set the curve to reflect those values exactly. You can add new points to the curve simply by clicking on it. The image window shows a preview of the change as you modify the curve. The change doesn't actually take effect until you click OK. For example, if you save the image before clicking OK, it's the old, unmodified image that will be saved. If you close the Curves dialog without clicking OK, then the changes will be lost.

![]() Often, it is easy to tell that the colors in an image are "off,"

but it's not easy to tell exactly what should be done to correct them.

The eye-dropper (or color-picker) tool can sometimes

be a help. This tool is used to sample colors in an image. When you

click on an image with this tool, the color of the pixel that you

clicked is selected as the current drawing color. More important for

our purposes here, a small dialog box pops up that displays the

red, green, and blue components of the color. In some cases, these

component values can help you determine how to set the curves

in the Curves dialog.

Often, it is easy to tell that the colors in an image are "off,"

but it's not easy to tell exactly what should be done to correct them.

The eye-dropper (or color-picker) tool can sometimes

be a help. This tool is used to sample colors in an image. When you

click on an image with this tool, the color of the pixel that you

clicked is selected as the current drawing color. More important for

our purposes here, a small dialog box pops up that displays the

red, green, and blue components of the color. In some cases, these

component values can help you determine how to set the curves

in the Curves dialog.

In Grokking the GIMP, Chapter 6, Corey Bunks gives some hints. If you think that a certain part of the image should be gray, for example, you can use the eyedropper tool to determine the actual RGB colors. If R, G, and B do not have the same value, you can use the Curves dialog to adjust one or two of the color curves. For example, if a pixel that should be gray has RGB values (100,130,100), you can try adjusting the green curve so that it goes through the point (130,100). That is, wherever the current green value is 130, it should be changed to 100. This will correct the offending pixel -- and hopefully will have a good effect on the rest of the image.

You can use other known colors in the image in the same way. For example, according to Bunks, for a "medium Caucasian flesh tone" the red level should be about 20% higher than the green level, and the blue level should be about 10% lower than the green level. The image shown below is a picture of a class trip in Australia (so we can assume that the skin tones should be about as medium Caucasian as you can get). This picture is taken from a collection of photos by Professor Kevin Mitchell. I chose it because the colors are rather bad. My corrected version is also shown.

When I worked on this image, I used the eyedropper tool to sample points in the road, which I thought should probably be closer to gray. I found RGB values of (148,140,165) and (49,41,123) in the road. The first sample led me to change the Blue curve to contain the point (165,145), which will change the first pixel to be almost gray. The RGB of (49,41,123) indicates that I might want the point (123,45) on the Blue curve, but the change seemed too extreme so I used something closer to (120,75). Finally, sampling the skin tones led me to boost the green mid-tones a bit. Then, after finishing with the curves tool, I decided to use the Levels tool to adjust the Value a bit in an attempt to bring some of the image out of shadow.

Transformation Tools

![]() The Gimp toolbox window contains five transformation tools, shown here. These are

the Rotate, Scale, Shear, Perspective, and Flip tools. Flip is the simplest: Click on an image with the

Flip tool to reflect it horizontally or vertically, depending on a setting in the

Tool Options. (Note: The tool options are shown at the bottom of the Toolbox window

when you double-click a tool.)

The Gimp toolbox window contains five transformation tools, shown here. These are

the Rotate, Scale, Shear, Perspective, and Flip tools. Flip is the simplest: Click on an image with the

Flip tool to reflect it horizontally or vertically, depending on a setting in the

Tool Options. (Note: The tool options are shown at the bottom of the Toolbox window

when you double-click a tool.)

The other four tools work all work in similar ways. Click with the tool on an image. A grid appears over the image with handles at the corners. A separate window also appears with information about the transformations and a few control buttons. Drag the handles to rotate, scale, shear, or apply perspective to the grid. For rotation, you can drag the center point of the grid to change the center of rotation. Then, to apply the same transformation to the image that you have applied to the grid, click a button in the extra window. (The name of the button, such as "Scale," depends on which transformation you are applying.) It would be nice to see the image transformed as you drag the handles, but transformation is presumably too slow an operation to allow that.

The perspective tool allows you to drag each corner of the grid independently.

In the picture at right, the upper right and lower right corners have been

positioned to transform the rectangular image into a trapezoid. This transformation

simulates a change of perspective -- it will look as though the right side of

the image is farther away than the left side. (Sort of; this is not

true perspective, just an imitation that often works OK.)

The perspective tool allows you to drag each corner of the grid independently.

In the picture at right, the upper right and lower right corners have been

positioned to transform the rectangular image into a trapezoid. This transformation

simulates a change of perspective -- it will look as though the right side of

the image is farther away than the left side. (Sort of; this is not

true perspective, just an imitation that often works OK.)

The tool options for the Rotate, Scale, Shear, and Perspective tools contain an "Interpolation" option. I suggest changing this from "Linear" to "Cubic" to get the highest quality image after transformation.

Note that transforming an image distorts the image and loses information because transformed pixels do not match up one-to-one to the original pixels. If you want to experiment to find the correct transformation, it's not a good idea to apply a series of many transformations to the image. Undo each transformation before trying another one, or your image will gradually turn into mush.

The Measure Tool

![]() The measure tool, which can also be found in the Gimp toolbox window, can be

used to measure distances and angles on an image. It's very easy to use -- just

click on one point, drag to another, and release. A line appears on the

image. The length of the line, in pixels, and the angle that the line makes

with the horizontal are shown at the bottom of the image window.

The measure tool, which can also be found in the Gimp toolbox window, can be

used to measure distances and angles on an image. It's very easy to use -- just

click on one point, drag to another, and release. A line appears on the

image. The length of the line, in pixels, and the angle that the line makes

with the horizontal are shown at the bottom of the image window.

The measure tool can be helpful when you need to scale one image to make it fit into a region in another image. Use the measure tool to measure the height of the image and of the region where you want to put it. Use a calculator to divide the region height by the image height. This gives a scaling ratio that you can use in the Scale Image dialog box. Similarly, measuring angles might help you to figure out how much rotation to apply to an image.

Layers and Layer Masks

Layers are one of the most important features of the the Gimp. Almost any

image composition task will involve creating and manipulation layers. Whenever

you are using layers, it's a good idea to keep the Layers dialog open on the

screen. This dialog has many features for working on layers. Clicking on a

layer name will make that layer active. All paint operations will apply to

the active layer. Double-click on a layer name if you want to type a new

name for the layer. Right-click to get a menu containing many layer operations.

Some of these operations are also available as buttons at the bottom of the

window.

Layers are one of the most important features of the the Gimp. Almost any

image composition task will involve creating and manipulation layers. Whenever

you are using layers, it's a good idea to keep the Layers dialog open on the

screen. This dialog has many features for working on layers. Clicking on a

layer name will make that layer active. All paint operations will apply to

the active layer. Double-click on a layer name if you want to type a new

name for the layer. Right-click to get a menu containing many layer operations.

Some of these operations are also available as buttons at the bottom of the

window.

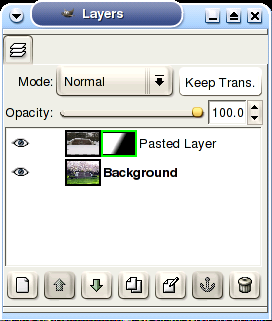

Above the list of layers are a few general control. The opacity slider can be used to make the layer more or less transparent. When the "Keep Transparency" toggle is off, you can paint or otherwise modify the transparent sections of the layer. If this toggle is on, it is impossible to paint on the transparent regions.

Each layer is represented by a small thumbnail image. To the left is an eye. Clicking the eye will make a layer invisible. Click again to restore the layer to visibility.

A layer can have a "layer mask." This is a grayscale image that can "mask out" parts of the image so that they are invisible or partly transparent. This can be better than simply erasing part of the image because you can always edit the layer mask to change the visibility of any part of the image. In fact, a layer mask is essentially an alpha channel for the layer in editable form.

To add a layer mask to the image, right-click the layer's name and select "Add Layer Mask" from the pop-up menu. The layer mask appears as a new thumbnail next to the image thumbnail. Layer masks can get confusing, so pay attention:

- Click the layer mask thumbnail if you want to edit the layer mask. In this state, any painting operation that you apply to the image window actually affects the layer mask rather than the image. You will see the changes in the layer mask thumbnail. Click back on the image thumbnail to edit the image.

- Sometimes you want to see the layer without the effect of the layer mask. Control-click on the layer mask thumbnail to disable the layer mask. You will see a red border around the layer mask thumbnail. Control-click again to turn the effect of the layer mask back on.

- Sometimes you want to see the layer mask in place of the image. Alt-click the layer mask thumbnail to do this. You will see a green border around the thumbnail. Alt-click the thumbnail again to see the image again. (Note that Alt-click won't work in KDE unless you have configured KDE to ignore Alt-clicks, as described in the previous lab.)

In the Layers Dialog shown here, the "Pasted Layer" has a layer mask. I have ALT-clicked the layer mask thumbnail so that the image window would show the layer mask rather than the image. The layer mask in this example is one used in the next project.

Winter-To-Spring Project

Here is an image that I made by combining two photographs of the entrance to Hobart and William Smith Colleges, one (from the Colleges' Web site) taken in the Spring and one taken by me in the Winter:

The first exercise for this lab is to make a similar Winter-to-Spring image of Scandling center. The Spring image (also from the Colleges' web site) is scandling_spring.jpg, and the winter image is scandling_winter.jpg. You want to combine these to produce an image in which the Spring version of Scandling fades into the Winter version. I will describe how I created my image.

The first problem was that the size and perspective of the winter and spring images didn't match. To get the size that I wanted, I ended up scaling the spring image to a larger size. I scaled the winter image to a smaller size. Then I copied-and-pasted the winter image over the spring image, and I used Layer / New Layer to make the pasted image into its own layer. The remaining work on this project was done on this layer. I repeatedly used the opacity and visibility controls in the Layer dialog to help me compare the two layers.

The two images did not immediately match up properly. The Spring image was shot from the side, while the winter image was shot straight-on, so the perspective in the two images looks different. I used the Perspective Transformation tool on the Spring image to fix this. (It took several attempts, and using the measure tool for some angle measurements helped.) Even then, the letters on the sign didn't register properly. So, I used the measure tool to take some vertical and horizontal measures on both images. This helped me determine the exact amount of scaling that I would need. (It turned out that the horizontal and vertical scale factors were different, presumably because the pictures were taken from different heights.) Eventually, I got the letters on the sign to register pretty well.

The final step was to add a layer mask to the winter layer and edit it. (Alternatively, I could have used a selection and cut away part of the image.) To add the layer mask, I right-clicked on the layer in the Layers dialog and selected "Add Layer Mask". To edit the layer mask, I clicked on its thumbnail in the Layers dialog, as described above.

I wanted a layer mask that would be fully opaque at one end and fully transparent at the other, with a fade-in between the two regions. To get this most easily, I used the Gradient tool. I selected the "FG to Transparent" gradient style (near the top of the list), and in the tool options I set the Repeat to "None", the Shape to "Linear", and the Opacity to 100%. Then, all I had to do was click the mouse on the image window, drag a short distance, and release. The direction and extent of the drag determine the direction and extent of the fade region between full transparency and full opaqueness.

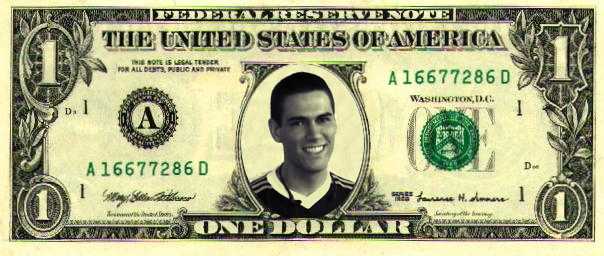

Funny Money Project

This is your second exercise for the lab. The goal of this project is to make an image that looks like a five dollar bill, but with another person replacing Abraham Lincoln. You should try to make the result as realistic as possible. The colors of the inserted image should be similar to those in the picture of Lincoln, the size should be appropriate, and the boundary where the two images join should not be too obvious. You can use a picture of yourself from the gallery of student pictures on the department's web site, or you can find a picture of someone else to use. The five-dollar bill image is five.jpg.

As an model, here is a similar image that I made when I taught the course a few years ago. In this image, I inserted Sean (a former computer science major) in place of George Washington on a dollar bill:

Sean's head was taken from a a color photograph. I used a variety of tools in this project. There is more than one way to approach this problem, but here is an outline of one process for creating this image.

- Using the Image/Mode submenu, I changed the Mode to Grayscale, and then changed it back to RGB. This produced an RGB image in which the R, G, and B components are all equal. This looks like a grayscale image, but it's actually an RGB image with three color channels that can be adjusted separately.

- Since the image is too dark, I used the Levels tool to adjust the Value.

- I then had to adjust the color of the image to make it match the colors of the dollar bill. I first used the Eye-dropper to test the colors in the dollar bill. My observation: The lighter colors tend to have similar amounts of red and green, with a lesser amount of blue (for example: 247,242,184 or 195,193,145). The darker pixels tend to have more similar amounts of red, blue, and green. I used the Curves dialog to adjust the colors in the picture of Sean. I adjusted the Red and Green curves based on my observations of the dollar's colors.

- Sean was the wrong size, so I had to scale his picture to fit. To find the scaling factor, I used the measure tool. I measured Sean and George Washington and used a calculator to compute the quotient of the two sizes. I used this quotient as the Ratio in the Image/Scale-Image command.

- I pasted the image of Sean into a new layer on the dollar bill image. I did Edit/Select-All on the photo of Sean, then Edit/Copy. I then did Edit/Paste on the dollar bill, opened the Layers dialog, and clicked the "New Layer Button" to make the pasted selection into a new layer.

- After dragging Sean into position, I cut away the part of Sean's picture that I didn't want. First, I cut back the opacity of the layer so that I could see what I was doing. I then made an elliptical selection, then inverting it, and using Edit/Cut. I also cut a little off the bottom of the ellipse. (Note: I used "guides" as demonstrated in class, to help make the elliptical selection. Remember that you can make a guide line by dragging from a ruler onto the image. You can drag the line off the image using the Move tool.)

- The background around Sean's head didn't look good, so I wanted to color it to match the background of the bill. First, I selected the background area around Sean's head, using various tools. With the selection in place, it is only possible to paint inside the selection. I then used the Clone tool to copy part of the general background area of the dollar bill to the area around Sean's head. (Remember: to use the Clone tool, first Control-click on the region you want to copy.)

- Finally, I fixed Sean's collar, which looked too bright. I did this by selecting the collar and filling it with a solid color using the bucket tool. I selected an appropriate fill color using the Eye-dropper tool.

And that's it. The result is not perfect but not too bad either.