| CPSC 120 |

Principles of Computer Science |

Fall 2025 |

Lab 2

Drawing and Interaction

Due: Fri 9/19 at the start of class

Introduction

This week's lab deals with drawing (shapes and colors) and

interaction (using the mouse position and responding to mouse clicks

and key presses).

Successfully completing this lab means that you are able to:

- decompose a complex scene into component shapes

- determine coordinates and sizes for shapes in a scene without

resorting to trial-and-error

- determine RGB color values for elements in the scene

- use core Processing commands: open a drawing window, clear the

window, set fill and stroke colors, draw basic shapes (ellipses,

rectangles, lines)

- create an interactive sketch that responds to the user moving

and clicking the mouse

- use the Processing API to learn about new things

Handin and Presentation Meeting

- Read through this section to know what you need to do to get

credit for this assignment.

Handin

Hand in a hardcopy (paper) of your worksheet in class.

To hand in your sketches:

-

Make sure that your name and a short description of the

sketch are included in a comment at the beginning of each

sketch.

-

Make sure that you've auto-formatted each sketch.

-

Copy the entire lab2a, lab2b, lab2c (also lab2c_extra if you did that extra credit),

and lab2d directories from your sketchbook

(~/cs120/sketchbook) to your handin directory (found

inside /classes/cs120/handin).

It is OK if you copy your files to the handin directory at the very

beginning of class.

Presentation Meeting

Review the assignments and

evaluation policy for information on proficiency-based grading and

how it works in this course. Presentation meetings are an essential

element of assessment and are required.

Presentation meetings for this lab will be the week of Sept

22.

Exercise #4 is the presentation problem. Come

to the presentation meeting prepared to discuss your sketch. You may

be asked to point out and explain how your code meets the requirements

of the problem, explain how portions of your code work, and/or apply

skills from the problem to a new situation (for example, to

demonstrate how to figure out coordinates and sizes for a different

scene).

Policies

- Read through this section so that you are aware of important

policies and procedures for this assignment.

Due Date and Late Work

Labs are due at the start of class. It is OK if you show up and copy

your files to the handin directory at the very beginning of class, but

this should take at most a couple of minutes and you should not spend

the class period finishing up the previous week's lab assignment.

Revise and resubmit applies for this lab. See

the "Second Chances" section

in the assignments and evaluation policy.

See the policy on late work and

extensions. In short: you must hand in at least an initial

attempt at an exercise by the deadline in order to be eligible to

revise and resubmit that exercise. A limited number of extension

tokens allows handin until the resubmit deadline without an initial

handin; see the policy for details. Late work is not otherwise

accepted.

Academic Integrity

Labs are a chance to practice and gain understanding as well as to

demonstrate what you yourself are able to do. They are

individual assignments.

You may not:

- Copy part or all of someone else's program or solution.

- Use someone else's solution to the same or a similar problem

"as an example" for your own solution, even if you make changes.

- Work collaboratively with other students to write a program or

solve a problem.

- Otherwise shortcut the process of creating programs for yourself.

The point of labs is to experience and learn the process of creating

programs — a particular program is a byproduct of gaining this

experience, not the primary goal of the assignment.

What you turn in for a grade must be your work

— your ideas and your effort — and

reflect your engagement with the process of creating

programs.

You may:

- Use and adapt examples from the course materials (slides and

examples from class and the textbook) or your own solutions from

earlier assignments.

- Get help in office hours and at Teaching Fellows. (Recommended!)

Within limits and with appropriate attribution, you may

also:

- Discuss how to solve a problem — but not write code

— with other students.

- Use other resources (such as reference books, websites,

YouTube videos, etc).

It is always your

responsibility to be diligent about making sure you fully understand

any sources used and any help received.

See the full academic

integrity and collaboration policy for more information on what is

allowed and how to provide attribution.

Use of AI

AI

may not be used for this assignment. This

includes, but is not limited to, using AI to write code.

AI

may not be used for this assignment. This

includes, but is not limited to, using AI to write code.

Preliminaries

- This section contains important information needed for the

assignment. Read through it before starting on the exercises so

you know what it contains information about, then come back for a

closer look at the details when they are relevant to your task.

Incremental Development

Build up your sketch one (small) piece at a time, running it

frequently to make sure it does what you want. This gives you

confidence that you are on the right track, and if something isn't

what you want, it is much easier to find and fix the problem if you

haven't added a ton of new code.

You can also practice incremental development by starting with a

simpler version of a task first. For example, exercises #1 and #2

below break down the task of creating an interactive sketch into two

pieces — first draw a static version of the scene, then add

the interaction.

Readability and Formatting Your Code

Most of the whitespace — spaces, tabs, newlines, and such

— in a program doesn't matter to the computer. (The only

requirement is to separate consecutive words with whitespace.) But

whitespace does make a big difference to the humans (including you!)

reading your program, and there are established conventions about

how to use whitespace to make your programs more

readable.

For example, you may notice that the lines of code inside setup

and draw in a sketch are usually indented:

void setup () {

size(400,400);

}

(In fact, lines of code inside any set of curly brackets

({}) are indented — we'll see other cases

later.)

Indentation is so useful that Processing (and many other

programming environments) provide an auto-format tool — choose

Edit→Auto Format from the menu. (Once you've written some code,

try messing up the indentation of one line or putting two lines on

one, and then Auto Format to see what happens.) It's also useful to

learn the keyboard shortcut — ctrl-T — so that you can

auto format frequently. (This can help you find some kinds of

syntax errors — if you auto format and things don't indent the

way you expect, there's likely a syntax issue near the beginning of

the incorrectly-indented part.)

Other conventions include using blank lines to visually group

related instructions (an

example) and using line breaks to keep lines from becoming too

long. How long is too long? 80 characters is commonly cited as the

upper limit because that's the typical width of a printed page

— longer than that means lines will wrap awkwardly when

printed. Tip: the following comment is 78 characters wide. Paste

it as the first or last line in your sketch and size the Processing

window so the editor is just wide enough to show the line without

having to scroll sideways. Then make sure to press Enter to add

line breaks to keep lines from extending past the edge of the editor

window. (It is legal to put a line break wherever whitespace is

allowed; pay attention to examples to get a sense of better

spots.)

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reference and Learning More

Processing provides a bunch of building blocks for sketches —

things like rect and ellipse and fill

and rectMode are part of this. How do you know what all

these building blocks are and how to use them? The traditional way

this information is made available to programmers is through an

API. ("API" stands for "application programming interface"; an

interface is where two different systems meet, and the API defines

how those systems can interact with each other.)

Access the Processing API by clicking on the link below, or from

within the Processing environment, by choosing Help→Reference from

the menu.

Try it out: go to the API, then look for the ellipse command

(type ellipse where it says "Filter by keywords..." or click

on "Shape" in the shortcuts to jump to the right section) and click on

the link to bring up the page about that command. You'll find

a description of the command, some examples, and its syntax.

This

is a useful way to refresh your memory about something you've already

used or to learn about how to use something new.

We'll cover some of Processing's functionality in class and the

book includes other elements not discussed in class, but you are

also encouraged (and sometimes required) to explore the Processing

API on your own to discover things not covered in class or the

book.

Exercises

-

Do the exercises in order.

-

Read through all of each exercise before you start on it. In

particular, note that the "to do this" steps are what you should

actually do to complete the exercise — don't just read the

first sentence of the problem, look at the example, and try to

write the sketch from there. Follow the steps!

-

Put your name and a description of the sketch in comments at the

beginning of each sketch. Also don't forget to Auto Format your code

before handing it in.

-

Be sure to save your sketch frequently (ctrl-S). (Every

time you run your sketch is good.) The editor does not

auto-save!

-

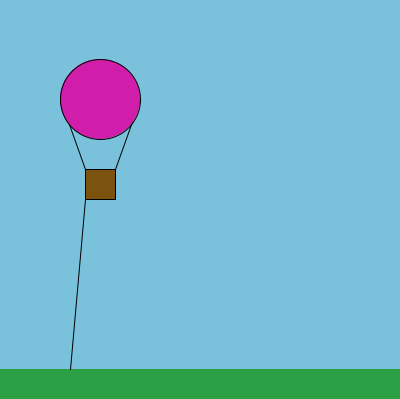

In this exercise you'll create a sketch which draws the scene

shown. Requirements for your sketch:

-

Name the sketch lab2a.

-

Make the drawing window 400x400.

-

Include

all of the elements shown — hot air balloon, tether (the

line extending down from the basket), grass.

-

The tether should

connect to the lower left corner of the basket and the cables

connecting the balloon to the basket should connect to the upper

corners of the basket as shown. Otherwise you don't need to match

the sizes, positions, and colors exactly, but you should aim for

something close.

To do this:

-

Complete the Exercise 1 section of

the lab 2 worksheet.

-

Create a new sketch named lab2a which draws the

scene. Start with the positions, sizes, and colors you

identified on the worksheet, then make corrections as needed.

You can use Tools→Color Selector to pick better

colors.

|

|

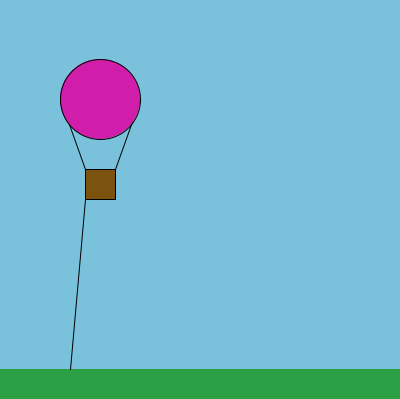

-

In this exercise you'll make the balloon move up and down

with the mouse as shown in the example. Requirements for your

sketch:

To do this:

-

Complete the Exercise 2 section of

the lab 2 worksheet.

-

Save a copy of your sketch from #1 with the name lab2b.

-

Modify lab2b to make the balloon move up and down.

You can do this incrementally — first make the change(s)

so the basket moves correctly, then update the rest of the

shapes so the whole balloon (including the tether) moves correctly.

|

|

-

In this exercise you'll create a sketch where the user can

use the mouse like a paintbrush — moving the mouse moves a

circle around the drawing window, leaving a trail of circles behind. Requirements for your sketch:

-

Name the sketch lab2c.

-

Make the drawing window 400x400.

-

The circle should be red and close to the size shown,

though you don't need to match the size exactly.

-

Clicking the mouse should clear the background.

To do this:

|

|

-

In this exercise you'll create an interactive sketch of your own design which showcases drawing and interaction. What the sketch depicts is up to you (here's a

chance to be creative!) but for full credit it must include the

following elements:

-

Name the sketch lab2d.

-

The scene must be original and created by you for this

exercise. While you might be inspired by an example from class

(such as the simple car) or another exercise in this lab (such as

the hot air balloon), you may not copy code from other

exercises in this lab, examples or solutions in the textbook or

from class, or other sources even if you then make some changes

— create your own version (such

as a fancier car) from scratch.

-

The scene must be recognizable as something. Include a

comment at the beginning of the sketch describing what it depicts.

The intent is that you should deliberately choose positions and colors

for the shapes — simply drawing a bunch of shapes at whatever

location they happen to end up at is not acceptable. Simplifying

things (like making a tree out of a rectangle and a triangle) is

fine.

-

You must include comments in your sketch identifying what

thing each drawing command or group of drawing commands is associated

with. For example, the comment

// hot air balloon

would be appropriate just before the commands that set colors and

draw the shapes for a hot air balloon. Also use blank lines to

separate the drawing commands for different elements in the

scene.

-

You must use at least 30 shapes. (That's 30 shape-drawing

commands, not 30 different kinds of shapes.)

-

You must use at least one ellipse, one rectangle, and one line.

-

You must use at least one arc, quad, or triangle. (That's one

total, not one of each.) Look up these shapes in the Processing API

to find out how to use them.

-

You must have at least four different compound things built

out of three or more shapes each. "Compound thing" just means that

you use several shapes to depict one thing; the hot air balloon from

#1 is an example (four shapes).

-

You must have at least one compound thing which moves with the

mouse (interaction), and you must use both mouseX

and mouseY. (This can be done with one thing that uses both,

or with two separate interactive things.)

-

You must use at least five different colors.

To do this:

-

Complete the Exercise 4 section of

the lab 2 worksheet.

-

Create a new sketch named lab2d which draws the

scene. Practice incremental development — add code for a few shapes at a time rather than writing everything before you run the program for the first time.

Extra Credit

Challenge yourself and earn extra credit by going substantially beyond

the required elements. (See

the assignments and evaluation

policy for more details on extra credit.) Some possibilities:

-

Make the red circle in #3 partially transparent. If you do

this, save a copy of your lab2c as lab2c_extra and modify

the copy — don't modify lab2c itself!

-

Create a more elaborate scene for #4:

-

Include many more

shapes.

-

Use more than the one required arc, quad, or triangle (that's

more than one kind of shape, not just two arcs instead of one) or make

use of the curve or bezier shapes. (Look them up in the API.)

-

Fancier mouse interaction — tie the size or color of some

things to the mouse movement, such as having a shape stretch wider

or shrink narrower as the mouse moves left and right.

-

Handle key presses — do something when a particular key is

pressed.

It's OK to add on to your lab2d sketch but be sure to

include a brief description of what you've done for extra credit in a

comment at the beginning of the sketch.