Section 1.6

The Modern User Interface

When computers were first introduced, ordinary people—including most programmers—couldn't get near them. They were locked up in rooms with white-coated attendants who would take your programs and data, feed them to the computer, and return the computer's response some time later. When timesharing—where the computer switches its attention rapidly from one person to another—was invented in the 1960s, it became possible for several people to interact directly with the computer at the same time. On a timesharing system, users sit at "terminals" where they type commands to the computer, and the computer types back its response. Early personal computers also used typed commands and responses, except that there was only one person involved at a time. This type of interaction between a user and a computer is called a command-line interface.

Today, of course, most people interact with computers in a completely different way. They use a Graphical User Interface, or GUI. The computer draws interface components on the screen. The components include things like windows, scroll bars, menus, buttons, and icons. Usually, a mouse is used to manipulate such components or, on "touchscreens," your fingers. Assuming that you have not just been teleported in from the 1970s, you are no doubt already familiar with the basics of graphical user interfaces!

A lot of GUI interface components have become fairly standard. That is, they have similar appearance and behavior on many different computer platforms including Mac OS, Windows, and Linux. Java programs, which are supposed to run on many different platforms without modification to the program, can use all the standard GUI components. They might vary a little in appearance from platform to platform, but their functionality should be identical on any computer on which the program runs.

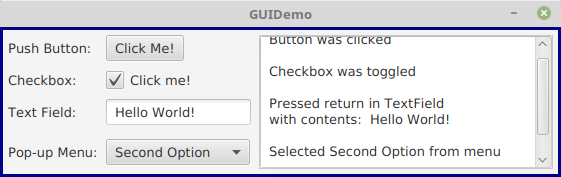

Shown below is an image of a very simple Java program that demonstrates a few standard GUI interface components. When the program is run, a window similar to the picture shown here will open on the computer screen. There are four components in the window with which the user can interact: a button, a checkbox, a text field, and a pop-up menu. These components are labeled. There are a few other components in the window. The labels themselves are components (even though you can't interact with them). The right half of the window is a text area component, which can display multiple lines of text. A scrollbar component appears alongside the text area when the number of lines of text becomes larger than will fit in the text area. And in fact, in Java terminology, the whole window is itself considered to be a "component."

(If you would like to run this program, the source code, GUIDemo.java, is available on line. For more information on using this and other examples from this textbook, see Section 2.6.)

Now, Java actually has three complete sets of GUI components. One of these, the AWT or Abstract Windowing Toolkit, was available in the original version of Java. The second, which is known as Swing, was introduced in Java version 1.2, and was the standard GUI toolkit for many years. The third GUI toolkit, JavaFX, became a standard part of Java in Version 8 (but but has recently been removed, so that it requires separate installation in some versions of Java). Although Swing, and even the AWT, can still be used, JavaFX is meant as a more modern way to write GUI applications. This textbook covers JavaFX exclusively. (If you need to learn Swing, you can take a look at the previous version of this book.)

When a user interacts with GUI components, "events" are generated. For example, clicking a push button generates an event, and pressing a key on the keyboard generates an event. Each time an event is generated, a message is sent to the program telling it that the event has occurred, and the program responds according to its program. In fact, a typical GUI program consists largely of "event handlers" that tell the program how to respond to various types of events. In the above example, the program has been programmed to respond to each event by displaying a message in the text area. In a more realistic example, the event handlers would have more to do.

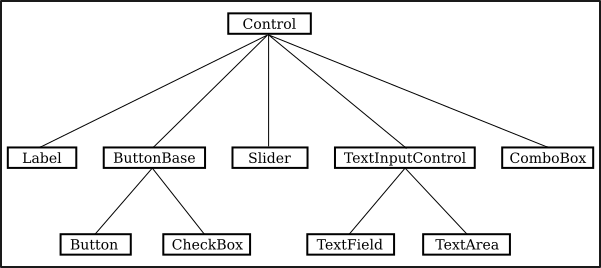

The use of the term "message" here is deliberate. Messages, as you saw in the previous section, are sent to objects. In fact, Java GUI components are implemented as objects. Java includes many predefined classes that represent various types of GUI components. Some of these classes are subclasses of others. Here is a diagram showing just a few of the JavaFX GUI classes and their relationships:

Don't worry about the details for now, but try to get some feel about how object-oriented programming and inheritance are used here. Note that all the GUI classes shown here are subclasses, directly or indirectly, of a class called Control, which represents general properties that are shared by many JavaFX components. In the diagram, two of the direct subclasses of Control themselves have subclasses. The classes TextField and TextArea, which have certain behaviors in common, are grouped together as subclasses of TextInputControl. Similarly Button and CheckBox are subclasses of ButtonBase, which represents properties common to both buttons and checkboxes. (ComboBox, by the way, is the class that represents pop-up menus.)

Just from this brief discussion, perhaps you can see how GUI programming can make effective use of object-oriented design. In fact, GUIs, with their "visible objects," are probably a major factor contributing to the popularity of OOP.

Programming with GUI components and events is one of the most interesting aspects of Java. However, we will spend several chapters on the basics before returning to this topic in Chapter 6.