Section 1.3

The Java Virtual Machine

Machine language consists of very simple instructions that can be executed directly by the CPU of a computer. Almost all programs, though, are written in high-level programming languages such as Java, Python, or C++. A program written in a high-level language cannot be run directly on any computer. First, it has to be translated into machine language. This translation can be done by a program called a compiler. A compiler takes a high-level-language program and translates it into an executable machine-language program. Once the translation is done, the machine-language program can be run any number of times, but of course it can only be run on one type of computer, since each type of computer has its own individual machine language. (In fact, Java also depends on the particular operating system under which it is running, since it must work with the operating system to perform certain tasks such as accessing the computer's hardware. But let's ignore that complication here.) If the program is to run on another type of computer it has to be re-translated, using a different compiler, into the appropriate machine language.

There is an alternative to compiling a high-level language program. Instead of using a compiler, which translates the program all at once, you can use an interpreter, which translates it instruction-by-instruction, as necessary. An interpreter is a program that acts much like a CPU, with a kind of fetch-and-execute cycle. In order to execute a program, the interpreter runs in a loop in which it repeatedly reads one instruction from the program, decides what is necessary to carry out that instruction, and then performs the appropriate machine-language commands to do so.

(A compiler is like a human translator who translates an entire book from one language to another, producing a new book in the second language. An interpreter is more like a human interpreter who translates a speech at the United Nations from one language to another at the same time that the speech is being given.)

One use of interpreters is to execute high-level language programs. For example, the programming language Lisp is usually executed by an interpreter rather than a compiler. However, interpreters have another purpose: They can let you use a machine-language program meant for one type of computer on a completely different type of computer. For example, one of the original home computers was the Commodore 64 or "C64". While you might not find an actual C64, you can find programs that run on other computers—or even in a web browser—that "emulate" one. Such an emulator can run C64 programs by acting as an interpreter for the C64 machine language.

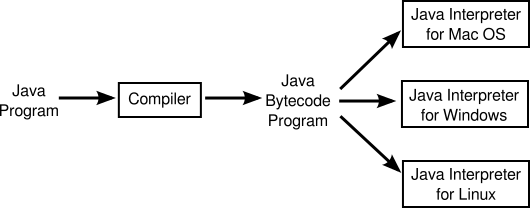

The designers of Java chose to use a combination of compiling and interpreting. Programs written in Java are compiled into machine language, but it is a machine language for a computer that doesn't really exist. This so-called "virtual" computer is known as the Java Virtual Machine, or JVM. The machine language for the Java Virtual Machine is called Java bytecode. There is no reason why Java bytecode couldn't be used as the machine language of a real computer, rather than a virtual computer. But in fact the use of a virtual machine makes possible one of the main selling points of Java: the fact that it can actually be used on any computer. All that the computer needs is an interpreter for Java bytecode. Such an interpreter simulates the JVM in the same way that a C64 emulator simulates a Commodore 64 computer. (The term JVM is also used for the Java bytecode interpreter program that does the simulation, so we say that a computer needs a JVM in order to run Java programs. Technically, it would be more correct to say that the interpreter implements the JVM than to say that it is a JVM.)

Of course, a different Java bytecode interpreter is needed for each type of computer, but once a computer has a Java bytecode interpreter, it can run any Java bytecode program, and the same program can be run on any computer that has such an interpreter. This is one of the essential features of Java: the same compiled program can be run on many different types of computers.

Why, you might wonder, use the intermediate Java bytecode at all? Why not just distribute the original Java program and let each person compile it into the machine language of whatever computer they want to run it on? There are several reasons. First of all, a compiler has to understand Java, a complex high-level language. The compiler is itself a complex program. A Java bytecode interpreter, on the other hand, is a relatively small, simple program. This makes it easy to write a bytecode interpreter for a new type of computer; once that is done, that computer can run any compiled Java program. It would be much harder to write a Java compiler for the same computer.

Furthermore, Java was created with the idea that some programs would be downloaded over a network. This leads to obvious security concerns: you don't want to download and run a program that will damage your computer or your files. The bytecode interpreter acts as a buffer between you and the program you download. You are really running the interpreter, which runs the downloaded program indirectly. The interpreter can protect you from potentially dangerous actions on the part of that program.

When Java was still a new language, it was criticized for being slow: Since Java bytecode was executed by an interpreter, it seemed that Java bytecode programs could never run as quickly as programs compiled into native machine language (that is, the actual machine language of the computer on which the program is running). However, this problem has been largely overcome by the use of just-in-time compilers for executing Java bytecode. A just-in-time compiler translates Java bytecode into native machine language. It does this while it is executing the program. Just as for a normal interpreter, the input to a just-in-time compiler is a Java bytecode program, and its task is to execute that program. But as it is executing the program, it also translates parts of it into the native machine language. The translated parts of the program can then be executed much more quickly than they could be interpreted. Since a given part of a program is often executed many times as the program runs, a just-in-time compiler can significantly speed up the overall execution time.

I should note that there is no necessary connection between Java and Java bytecode. A program written in Java could certainly be compiled into the machine language of a real computer. And programs written in other languages can be compiled into Java bytecode. However, the combination of Java and Java bytecode is platform-independent, secure, and network-compatible while allowing you to program in a modern high-level object-oriented language.

There are even some other programming languages that compile into Java bytecode. The compiled bytecode programs can then be executed by a standard JVM. New languages that have been developed specifically for programming the JVM include Scala, Groovy, Clojure, and Processing. Jython and JRuby are versions of older languages, Python and Ruby, that target the JVM. These languages make it possible to enjoy many of the advantages of the JVM while avoiding some of the technicalities of the Java language. In fact, the use of other languages with the JVM has become important enough that several new features have been added to the JVM specifically to add better support for some of those languages. And this improvement to the JVM has in turn made possible some new features in Java.

I should also note that the really hard part of platform-independence is providing a "Graphical User Interface"—with windows, buttons, etc.—that will work on all the platforms that support Java. You'll see more about this problem in Section 1.6.